For a man who creates fake people, Victor Riparbelli is reassuringly real. With London at his feet, he has shunned the fancier restaurants favoured by many chief executives and plumped for the pretty Narrowboat pub on the Regent’s Canal in Islington, north London, owned by Young’s. The waterside location makes a lovely setting for a hot summer’s day.

It also holds lots of memories for the young entrepreneur, who used to live around the corner. He was a regular at the Narrowboat with his Synthesia co-founder Steffen Tjerrild through good times and bad.

Synthesia is everything that Hollywood fears. It uses artificial intelligence to create lifelike human faces and speech that are almost indistinguishable from real video but do not need cameras, actors or film studios. It is not a household name, but the bartender pulling our pints has heard of the business and she is impressed that Riparbelli has come in.

The high-quality, low-cost films are aimed at corporate clients for training, marketing and communications. Synthesia’s technology has been used for adverts, including to make David Beckham speak nine languages to raise awareness of malaria and repurposing a Just Eat ad featuring Snoop Dogg to make the rapper say the words Menulog, the name of the company in Australia, by changing his lip movements.

Walking into the Narrowboat gives Riparbelli a visceral reaction. We both opt for a pint — shandy for me — and sit down at an inside table. It’s less scenic than the canal view, but better to record a quiet chat. The small balconies are getting going, despite it being a weekday lunchtime.

“We’ve had quite a lot of beers here discussing why we’re definitely going to go bankrupt next week and why we think this could become a $20 billion company,” he reminisces.

“There was one day where we’re trying to raise the second round of funding and we’d been going for nine months. Nobody wanted to fund it. But we had this one fund left who had said that they thought it was interesting.”

The call was a disaster. “I just completely bombed it. It’s probably my worst pitch performance ever. We were very desperate, which is exactly how you don’t want to sound when you’re pitching to an investor. I just totally, royally, screwed it up.”

The pair dealt with the rejection by trying to laugh it off in the pub. “We did manage to eventually solve it a few weeks later. I’ve had many such situations but this is probably the most intense one.

“But we also came here when we closed the round. And managed to hire an amazing AI researcher, which we thought was completely impossible. And won our first customer. So this place has a lot of good memories and a lot of bad memories.”

The food at the Narrowboat is proper pub grub. Our starters are a beige pile of fried squid for Riparbelli and a summer salad for me.

Those days of rejection and the “desert walk” of scratching around for capital are long gone. Riparbelli, 32, and his co-founders have raised $150 million since the company was established in 2017. Its latest series C funding round in June this year raised $90 million and Synthesia is one of London’s unicorns, valued at over $1 billion. It employs almost 400 people in the UK, the US and Denmark.

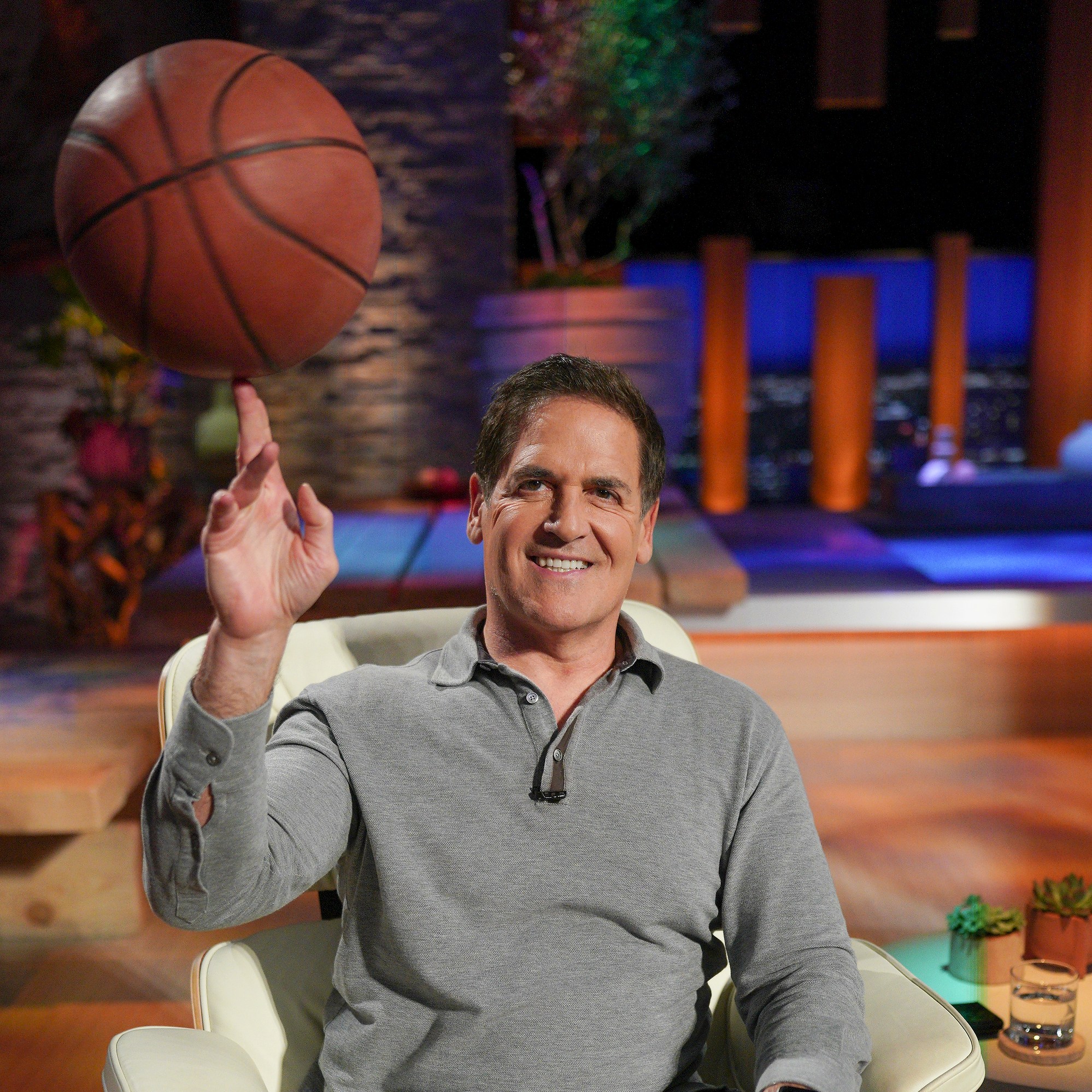

Initially the company was funded with cash the founders had made investing in cryptocurrencies. Then they sent a “cold email” to Mark Cuban, the American billionaire who appears on Shark Tank, the American version of Dragons’ Den. He replied within four minutes, and 14 hours of back and forth later he agreed to put in $1 million, assuming the due diligence checked out. He kept his word.

• AI investment cuts threaten UK’s global leadership

Synthesia’s later backers include Accel, Nvidia and Kleiner Perkins.

Now, Riparbelli’s team are trying to make their avatars more expressive and more natural, and to improve their voices.

“These technologies are going to get better and better,” he says. “They’re still far from being able to produce a Spielberg film, but they’ll get good enough that at some point, all the world’s YouTube creators who today are limited to filming themselves, talking to the camera, making a prank video outside, they’re going to be able to get way better tools for storytelling.”

Following a stint at Stanford University in California, Riparbelli chose to leave his native Denmark to set up a company, not knowing what it would be.

“Some of the positives that I took with me are the classical tropes of Silicon Valley. I was thinking really big, very ambitious, very driven, working very, very hard. In Denmark I just didn’t feel like that was the environment around me: it’s more about work-life balance than doing great things.”

Our mains arrive. We have both gone for chicken fricassée, a delicious dish served with mushrooms, garden peas and pan-fried gnocchi.

Riparbelli ended up in the UK because it was hard to get a corporate visa to the US and “I knew some people here, it felt closer to home”. It was 2016 and Oculus headsets, made by Meta, had just been launched, which drew him to the world of video, and of virtual and augmented reality.

The lightbulb moment came when he met his other co-founder, Professor Matthias Niessner, who had written a research paper, showing AI producing hyper-realistic videos.

“It felt like I saw magic for the first time,” Riparbelli smiles. “I have a very obsessive personality. It’s one of my strengths and my weaknesses. I just got obsessed with this idea.”

The founders developed two theories that form the basis of the company. “The first one is that with these technologies, the marginal cost of creating content is going to go to zero, not just in dollars, but in time and skill, because the production process can be digitised,” Riparbelli says. “In three years, you’re going to be able to produce a Hollywood film from behind your desk without really anything else, just your imagination.

“The second is, as we increasingly can generate content with code instead of having to physically record it, what we know as video today is going to change completely.

“Video today is a linear medium and it’s a product of the constraints you have in the production process. You have to film things with a camera, you put it onto your computer, then you can’t change it. And if you want to shoot something else, you need to go out in the real world and shoot it.

“It’s very different from most of our other digital experiences, with text, for example. Video or whatever it’s going to evolve into, I think, is going to be very different.”

It wasn’t until 2020, after a lot of experimenting, that Synthesia started to feel like a “real company”, he says, when the company found a “real use case” that 50,000 businesses — including a third of the Fortune 100 companies, it claims — now buy.

“Those are not people who are buying it because it’s AI and it’s cool. They’re like, ‘We try to give people 30-page manuals to make sure that they’re safe at work, and even if we force them to sit down, really they don’t remember. So now we can make a really high-quality video instead’.”

The unions representing Hollywood writers and actors might have something to say about these bold statements. They recently led long strikes over studios’ use of AI and the potential impact on jobs.

Riparbelli argues: “I don’t think that we’re going to move into a world where everything is just going to be completely AI-generated content. I think we’ll value real human content more. People are not going to want to watch just super-crappy movies made with AI, just because they’re made with AI.”

• Ian Holm’s widow backed ‘digital necromancy’ for his Alien resurrection

On top of the concerns over creative industry jobs, there are well-founded fears about deepfakes and misinformation.

“It is so important to think about safety from day one,” Riparbelli says. “We have a very ethical framework that we take very seriously. But there’s also an element of, like, no truly transformative technology has not gone through that.

“Eighty years ago radio novellas was the thing parents were very scared about, teenagers being in their rooms, listening to the radio, listening to stupid content. When I was young, I remember playing video games. The fear was if you play too many of these video games, you’re going to end up like a school shooter or a criminal. I think it’s very important to have that perspective with these things. But that’s not an excuse to not take it very seriously.”

Riparbelli compares AI in video to Photoshop or the drum machine, synthesiser and software in music creation. He is a huge techno fan.

“You’re not limited by anything else, just your own creativity. That upended the music industry big time from the 1990s up until the way it is today, where it’s more about who makes the best music, not who has a dad who works in the record industry and has a studio you can use and knows the right people.”

• Big Tech is booming. Here’s how London can benefit

Starting a company can be lonely. Riparbelli is one of a group of founders building innovative AI businesses in the UK. As we meet he has dinner plans with the founders of two other London AI companies, Wayve and Eleven Labs. They can share frustrations and experiences, the brutal realities of start-up life.

He does not see Synthesia becoming an AI film studio, although he won’t rule it out. At the moment the vision is focused on communications, with the end goal to build “a really big company” headquartered in Europe.

“In 2024 and beyond, people want to watch and listen to their content much more than they want to read,” Riparbelli. “The reason we’re not watching and listening to almost all our content today is because it’s just not feasible to create video and audio content for everything. With these technologies, that’s going to be possible.”

CV

Age: 32

Education: BSc from the IT University of Copenhagen, with a term spent at Stanford (where he met his co-founders)

Career: 2012-2015: owner of RBLI, a consultancy specialising in digital marketing and search engine optimisation 2014-2016: growth and product marketing at Founders, the biggest start-up studio in the Nordic countries 2016-2017: co-founder of Immersive Futures, a consultancy specialised in computer vision, augmented reality and virtual reality. Worked with the UK government to devise and execute a strategy to develop a strong VR/AR industry in the UK, including setting up London’s first high-quality volumetric capture studio, Dimension 2017-now: CEO and co-founder of Synthesia

Lives: London

Receipt

2 Sparkling water £10.701 Large cordial and soda £2.601 Summer salad £132 Chicken fricassée £381 Fried squid £8.501 pint Peroni £7.251 pint Peroni shandy £7.25

12.5 per cent service charge £10.91

Total £98.21